This was a guest post originally written for Conservation Biology Institute. The original post can be found by clicking on this link.

It’s been over a year since the viral article, The Ocean is Broken, caused waves in online forums and across the blogosphere. The article details Ivan McFadyen’s encounter with a polluted, seemingly lifeless ocean on a recent ocean crossing between Australia and Japan on his sailboat. He contrasts this with previous crossings where life seemed to be bubbling forth from the depths, plentiful and animated. His conclusion? The ocean is broken.

I read this article near the beginning of a three-year sailing trip down the Pacific Coast from Oregon to Panama and back again. We are not marine biologists and we have not been systematic or scientific about our observations. We do not know the stretch of ocean that McFadyen traversed and we’ve sailed only a very small portion of the vast blue space, but our life does offer us a unique perspective.

For nearly a year I’ve been looking at the ocean through the lens of that question: Is the ocean broken?

When we began our journey, everything about the sea was new to me. I was like a newborn, my surroundings slowly coming into focus, engulfed by mystery and wonder and questions, so many questions. There was this whole parallel universe operating on a totally different set of rules and relationships that were completely unknown to me. I expected to feel unequivocally alone on the sea, but that was not the case.

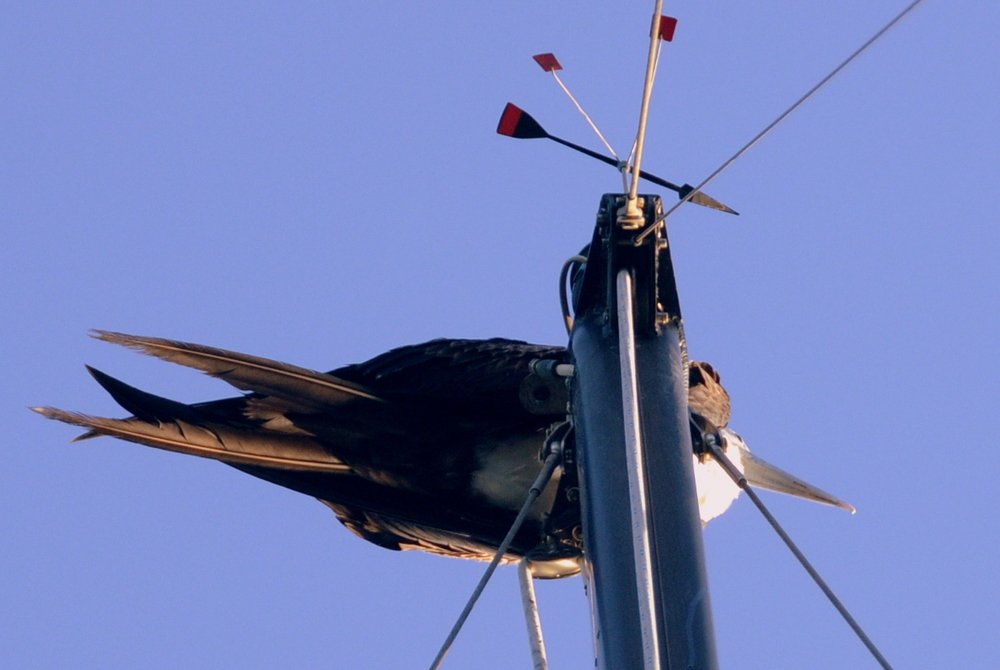

Off the coast of Guatemala and El Salvador we encountered hundreds of turtles and found it nearly impossible to avoid them in the wide open expanse of water. Almost every time we go out sailing, dolphins rush to play at our bow. Birds dive bomb the water around us at anchor, battle to sit atop our mast, and hitch a ride while we sail. Manta rays leap and fish skip like pebbles on the surface of the water, avoiding the invisible jaws that pursue them. Glowing blue orbs float on the surface of the calm sea. Squid launch themselves onto our boat in the middle of the night. Snakes somehow manage to sidle their way onboard. Possums clamber into our dinghy. Mud daubers nest in our bookshelves. The humpback whales in Western Panama are feeding and birthing their calves in anticipation of a southern migration while we prepare to migrate north

Humpback Whale in the Sea of Cortez.

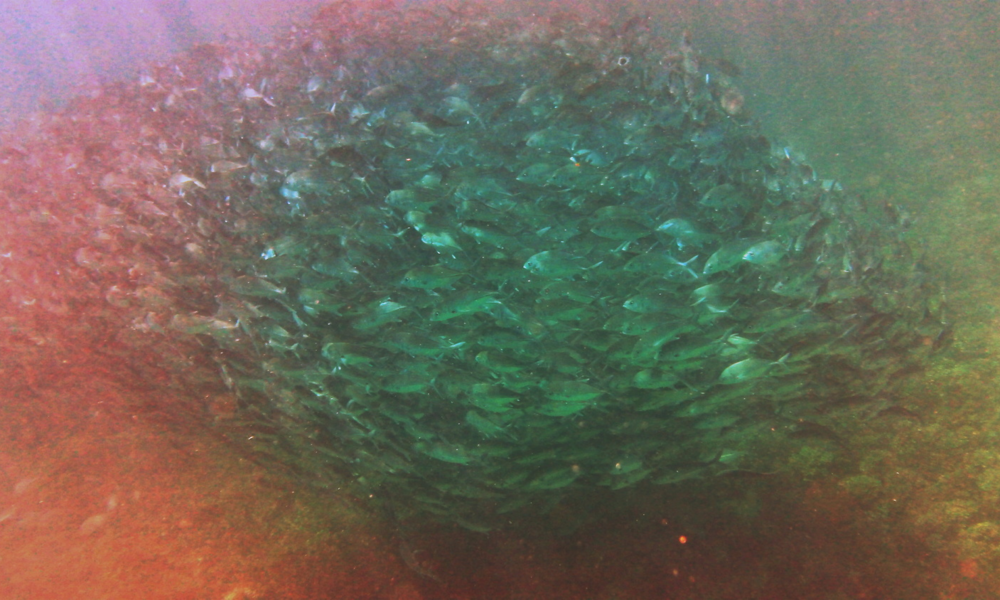

A School of Pompano at Isla Granito De Oro in Western Panama.

Frigate hitching a ride (and bending our wind vane in the process)

This is how we spot turtles.

Hundreds of Dolphins off of the coast of California.

Blue Footed Boobies at Isla Isabel in Mexico.

Grey Whale in the Sea of Cortez.

The sea is the primary source of food for many communities we’ve encountered, and it still manages to sustain local economies. Fishermen who, since the age of 15 have spent 330 days a year fishing in the coastal Panamanian waters inform us that there have always been fish, Gracias a Dios. Our friends at a nearby island have been fishing the same point for decades in the hour before sunset and always return home with something for dinner.

We have found that life, on our particular ocean transect, is plentiful and vibrant, but it’s not hard to call forth memories that cast a shadow.

While eating lunch up an estuary in El Salvador, a young timid girl approached us and, peeling back a small plastic bag, revealed a dozen fragile turtle eggs. They’re very delicious, she explained. That afternoon, on the way back to our dinghy, we walked past a table displaying hundreds of shark fins drying in the sun. In a country where the average daily wage is reportedly $10, in a world where I am ten steps removed from the extractive industries that sustain me, can I really judge from my privileged position?

We pulled our dinghy to shore at Isla Uva, part of the Coiba protected marine sanctuary in Panama, and waded through plastic trash up to our knees. We packed out what pieces would fit into our two dinghies and towed it to a nearby community for proper disposal, only to discover that their trash solution involved burning the rubbish in a soccer field and dumping it down a nearby ravine. The charred remnants were flushed out to sea with the next big rain, along with all of our good, though naïve, intentions.

All of that is trash lining the shores of Isla Uva. Flushed out to sea during the next high tide.

This little guy was surrounded by mountains of trash.

We’ve heard persistent accounts of over fishing followed by stories of how good the fishing used to be. It was the same song the whole way down the coast, sung in rounds. The song began in Southern California and repeated again on the outside of Baja, the Sea of Cortez, mainland Mexico, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and now Panama. Panama appears to be on its first chorus, while those farther North have been repeating this song for twenty years or more. Many of the species descriptions in our fish identification book are accompanied by the words, “Once prolific but have been overfished and their population is now significantly depleted and reaching extinction.”

My godmother, who sailed these waters many years before, basked in her memories of a particular bay in Northern Mexico: The water so clear, shrimp the size of your fist, fish so plentiful, beaches so clean, mangroves so lush, the solitude so profound. And I would, with longing for her memory, inform her that the water is now foul, shrimp the size of your finger, fish harder to find, beaches littered with trash, mangroves retreating.

My relationship with the Pacific Ocean has really only begun – can I measure the integrity of the ocean against other people’s memories? Their stories? Their nostalgia? Can you measure it against mine?

The ocean is not broken or dead, not in my opinion anyway. We are pushing her to the brink, we are abusing her abundance, but there is life in her yet. That’s not to say we can continue on with business as usual. All is not lost, but all is not well. We cannot dissociate ocean health from the socio-economic conditions that result in poached turtle eggs, overfished reefs, polluted water, trashed beaches. It’s a messy, complex web of cause and effect, one from which you and I cannot neatly disentangle ourselves. If we want to improve the health of the ocean, we need to keep an eye towards shore. We need to investigate and challenge and ultimately change the systems that encourage us to take more and leave less.

Harmony, as always you have such a soulful and beautiful voice. I, too, am cautiously optimistic about our oceans. Thank you for this perspective!

Thanks for the kind words, Brittany. I’m cautiously optimistic, but that optimism is slowly eroding with all of the scientific studies I’m reading and documentaries I’m watching. Some days I’m so hopeful and some days I feel like we’re all doomed.

Meanwhile in California we outlaw plastic bags and blame the plastic problem on ourselves. Americans were once the same polluters until an enlightenment in the 70’s. How can we become environmental missionaries to the third world ?